The world is currently going through various difficulties, including conflict, COVID-19, inequality, and climate change, which are leading to more poverty and hardship. The progress made towards eradicating extreme poverty has slowed down, and the number of people needing humanitarian aid is increasing. Climate change-related disasters and humanitarian crises are also on the rise and are expected to worsen in the future. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has predicted that 339 million people will require lifesaving humanitarian aid in 2023, which is 65 million more than in 2022. In the Horn of Africa, approximately 20.2 million children are at risk of severe hunger, thirst, and disease, compared to 10 million last July, and one person is dying every 48 seconds in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia alone. The Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit is anticipating an official famine declaration in Somalia between April and June 2023, just as international support is likely to decrease due to a lack of adequate funding.

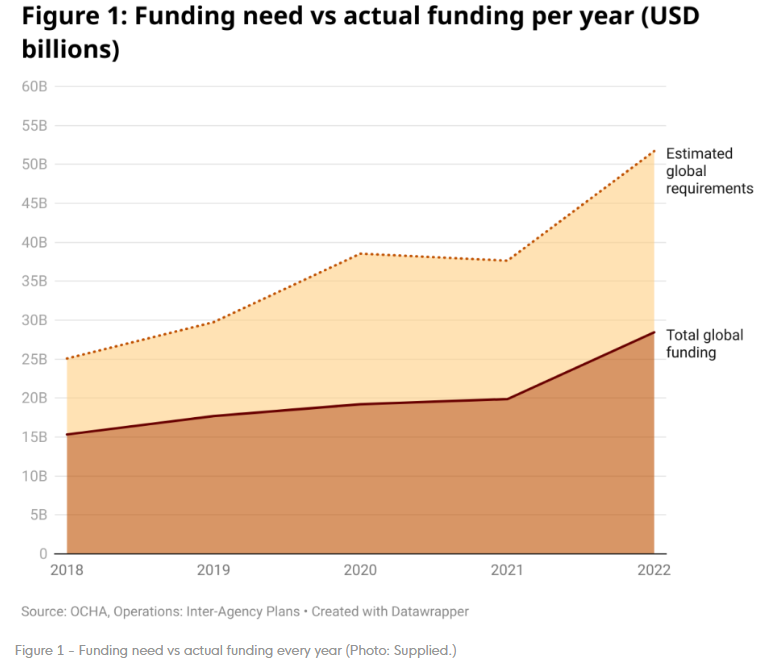

OCHA has requested USD51.5 billion for life-saving aid in 2023, which is the highest amount requested to date. However, the funding for humanitarian aid has fallen short by 44% over the last five years. This failure of wealthy countries to meet their moral obligation to the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people is alarming. Australia played a leading role in responding to the 2011 famine in the Horn of Africa, providing one of the largest-ever international disaster relief contributions of AUD112 million. One of the key lessons learned from that response was that waiting until the famine was declared was too late, resulting in many lives lost. We must not repeat this mistake. As the looming famine in East Africa and the ongoing crises raise humanitarian needs to unprecedented levels, a coalition of 26 Australian development agencies has formed to combat the crisis.

A group of 26 leading Australian development agencies has formed the Help Fight Famine Coalition in response to the looming famine in East Africa and the escalating polycrisis causing record levels of hunger and humanitarian needs. The coalition launched its latest report and new polling at Parliament House on March 20, 2023, calling on the federal government to increase its humanitarian and aid funding in the upcoming budget. The report and polling revealed a significant gap between the growing support for aid to the region by everyday Australians and Australia’s low humanitarian and declining aid funding over the past decade. The polling, conducted by YouGov with over 1,000 Australians, showed that public support for Australian government funding for overseas aid to developing countries has increased from 52% in 2019 to 57% in 2021 and to 60% in 2023. This consistent increase in support is a positive development amidst Australia’s cost-of-living crisis, and in line with findings from the Development Policy Centre that Australians increasingly support assistance to developing countries in the aftermath of COVID-19.

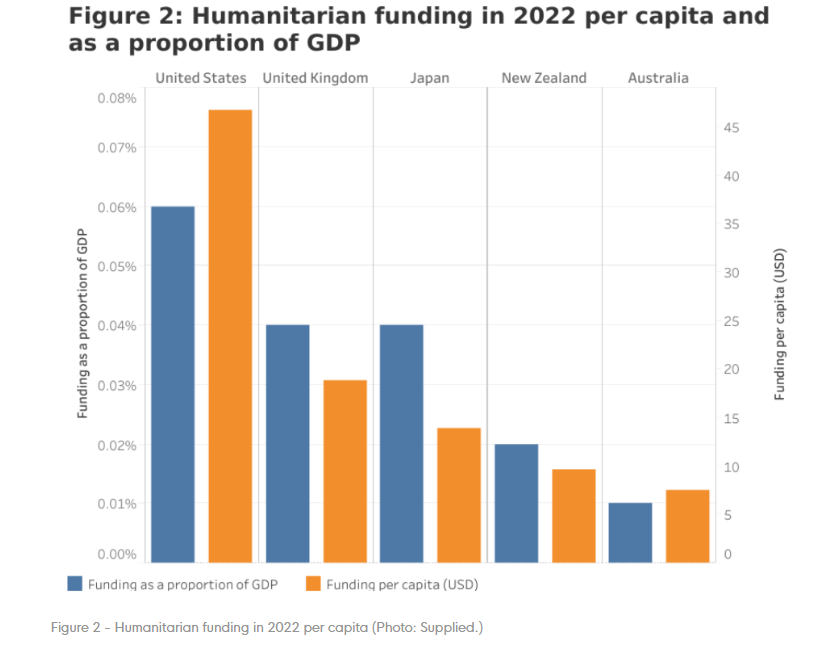

Despite being one of the wealthiest countries in the world, Australia’s humanitarian funding has remained relatively low over the past ten years, with only minor increases in recent years. According to data from OCHA, in 2022 Australia contributed only 0.01% of GDP to humanitarian aid, which is half of what New Zealand contributes, a quarter of Japan and the UK, and one-sixth of the United States’ contribution when proportional to GDP. Although this data does not represent all humanitarian funding by countries, it is still a useful point of international comparison. The Australian government has allocated AUD$25 million for the looming famine in the Horn of Africa, with only AUD$5 million specifically earmarked for Somalia. While this is a good start, with global funding for the crisis about to decline, more action is needed.

Australia’s total overseas development assistance record is equally disappointing. Over the past ten years, the country’s aid has decreased by over AUD$1.6 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars, leading to aid dropping to just 0.2% of gross national income (GNI) in 2022-23. This amount falls well short of the OECD Development Assistance Committee’s average of 0.33% of aid-to-GNI. The government committed an additional AUD$1.4 billion over four years to aid in the 2022-23 federal budget, but this increase is not enough to keep up with inflation or to reverse the downward trend in aid-to-GNI. Moreover, none of this extra aid was allocated to address the looming famine in East Africa. The Help Fight Famine Coalition believes that the 2023-24 budget offers a great opportunity for the Australian government to create a better future and respond to the significant challenges of our time. The Coalition is hopeful that the new government can bring positive energy, strategic vision, and a recognition of the popular sentiment towards aid to reverse Australia’s disappointing aid record over the past decade.

The Help Fight Famine Coalition is requesting additional funding to prevent a humanitarian catastrophe in areas like the Horn of Africa, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Syria. Specifically, they are seeking AUD$110 million to address the hunger crisis in these regions. Additionally, the coalition is urging the government to double the annual allocation to the Humanitarian Emergency Fund to AUD$300 million, allocate AUD$200 million annually for three years to global food security, and raise the aid budget to 0.5% of GNI, with this target to be established as law. The coalition believes that there is strong public support for the government to prioritize humanitarian and aid assistance, as all lives are equally important.

According to Josie Lee, the Policy and Advocacy Lead at Oxfam Australia has been advocating for social, climate, and First Nations justice for two decades. This article was originally published on Devpolicy Blog, which is hosted by the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.